The Wrist Pain That Lingers: What to Know About Ulnar-Sided Injuries

⌚️ read time: 5 minutes

When people talk about wrist pain, they’re usually thinking about the thumb side.

De Quervain’s. Carpal tunnel. Scaphoid fractures. Arthritis at the base of the thumb.

But pain on the opposite side of the wrist — the pinky finger side of the wrist — is just as common. And often far more confusing.

Hand surgeons typically lump it all together and call it ulnar-sided wrist pain. While it usually doesn't demand surgery, it can quietly drain your grip, weaken your strength, and linger for months or years if left unchecked.

A Small Zone Packed with Complexity

The ulnar side of the wrist may look simple at first glance. But nothing could be further from the truth.

In fact, that's kind of why we lump it all together as ‘ulnar-sided wrist pain.’ There’s so much anatomy on this side of the wrist, it’s often just easier to put it all in the same bucket unless more specificity is necessary.

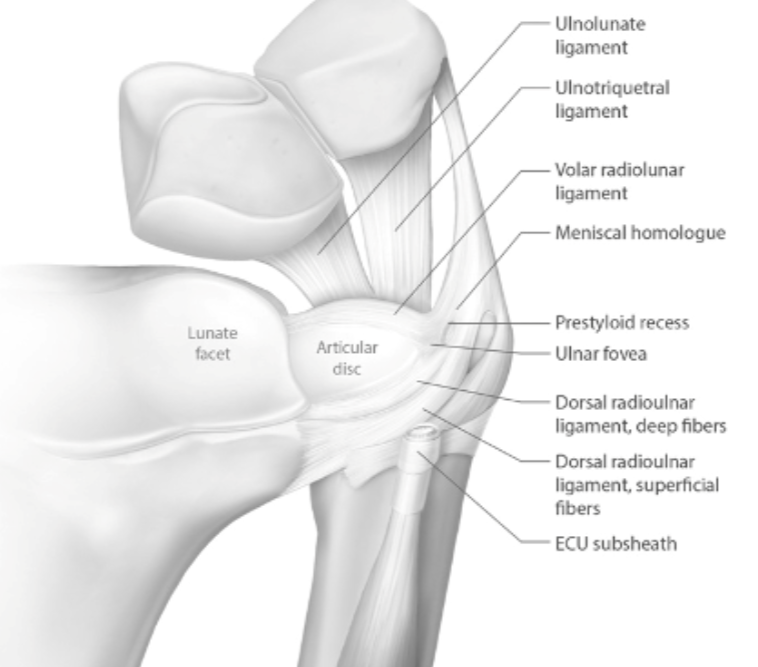

The core structure of this side of the wrist is the TFCC — the triangular fibrocartilage complex (say that five times fast). Think of it like a meniscus in the knee. Or a soft donut-shaped pad between the wrist bones and forearm bones. It serves as a cushion for this joint.

Surrounding the TFCC are the distal radioulnar joint (a joint that lets your forearm rotate), the ECU tendon (which stabilizes the wrist during extension and side-to-side movement), and a tight weave of ligaments that keep the whole system from shifting out of place.

The problem is, when just one of these tissues is irritated, the symptoms often overlap and spread throughout the whole system. Which, again, is why isolating the exact source can be tricky.

The Most Common Causes

Most cases of ulnar-sided wrist pain aren’t caused by a dramatic fall or an obvious tear.

They’re caused by something more subtle — a tendon that’s been overloaded, a joint that’s been stressed at the wrong angle, or a structure that’s been wearing down over time.

TFCC irritation is by far the diagnosis I see most. It often shows up as pain with grip and forearm rotation. It is most felt by the patient with activities like opening jars, turning keys, or lifting a pan. I also see this commonly in golfers, tennis players, and electricians. Repetitive twisting and gripping is a recipe for muscle imbalance that leads to TFCC strain.

ECU tendinitis is another common cause of ulnar-sided wrist pain. This tendon’s primary function is to extend the wrist, but all of its cross-connections make it vulnerable to irritation in myriad ways. In more advanced cases, this tendon can even shift out of its groove, resulting in a painful snapping sensation.

Ulnar impaction syndrome is probably the last of the ‘big 3’ when it comes to ulnar-sided wrist pain. This syndrome typically begins at the end of growth, when the ulna ends up slightly longer than the radius. You can imagine, if one forearm bone is a bit longer than the other, this puts extra pressure on one side (the ulnar side) of the wrist joint where everything comes together. We see this most with impaction-type pain during push-ups, yoga planks, or heavy lifts.

Why It Lingers

Ulnar-sided wrist pain is almost always a good news/bad news situation. The good news? It’s rarely urgent. The bad news? It typically lasts WAY longer than expected.

The internet has this nasty habit of convincing all of us that most aches, pains, and injuries should be better by 6 weeks.

When patients come to me with this pain syndrome? I warn them about the next 6-9 months.

Why? There are a few reasons.

The first is the simple fact that this doesn’t hurt as much as other injuries, so most people never truly rest it. They just sort of change how they use it and work through the pain. This is fine in some cases, but most of the time it will not result in rapid symptom resolution.

The second is the anatomy itself. As we've discussed, the anatomy on this side of the wrist is highly complex, but it is also heavily involved in stabilizing the wrist during rotation, as well as accepting heavy loads with any sort of gripping activity.

This results in multiple cross-connections that can be hard to rest in multiple planes of motion across multiple activities. A recipe for lingering injury that takes longer than average to heal.

The last is the tissues involved. This side of the wrist is made up almost exclusively of tendons and ligaments. These are collagen-heavy structures. As great as collagen is, it is extremely slow to heal. The average collagen turnover time in our body is on the order of 6-12 months. Nothing like the 6 weeks it takes most bones to heal.

So yet again. All a recipe for a slowly healing, annoyingly lingering type of pain.

What Treatment Looks Like

Remember the good news. Surgery is almost never the first answer here. But “just live with it” isn’t the answer either.

The best outcomes come from structured, progressive care. That means identifying the exact movement or load that’s causing trouble, then modifying it or bracing against it — not stopping everything.

Oftentimes, this comes in the form of a brace or a strap to unload the ulnar side of the wrist, coupled with a rehab program to rebalance and re-strengthen the wrist. We do find that a subtle, progressive imbalance of wrist forces (think of all the repetitive activities we like to do) will put the ulnar side of the wrist out of whack and susceptible to these types of injuries.

This 1-2 punch of a period of bracing/rest, followed by structured rehab, is exceedingly powerful for accelerating healing on this side of the wrist.

When patients come in to see me with this pain, many quickly ask me about cortisone injections. Certainly, these can help in specific cases — usually for ECU sheath inflammation or a reactive TFCC — but without fixing the mechanics, the pain often returns.

If we can wait, I prefer to flip the script. Let’s calm things down with a short period of bracing and rest, then work through structured rehab…and if you still have pain at the end or there’s a plateau you can’t quite get over? Boom. Hit it with that steroid injection.

And the last resort is surgery. True surgery is reserved for structural abnormalities, persistent instability, or severe impaction that hasn’t improved with conservative care. But most of these are big surgeries with big recoveries that should only be undertaken if truly necessary.

Takeaways:

Ulnar-sided wrist pain is both exceedingly common yet highly complex.

The TFCC and ECU tendon are the two ulnar-sided wrist structures that are the most frequent culprits.

Recovery requires identifying the exact aggravating motion, allowing for a period of rest, and then retraining the involved structures.

As with many topics in surgery, each of the above conditions on the ulnar side of the wrist is its own rabbit hole. While this article serves as a general overview, I’ll be sure to use future articles to go even more in depth on the specifics of each.